Agreed. These national maps may be useful as guides to when certain routes were in existence, but we’ll have to supplement them with more local maps for the geometries and written publications for the start and end dates.

In the past, some OSM mappers (particularly NE2) have mapped auto trails as route relations based on old guidebooks in Google Books. But since OSM only maps extant road infrastructure, the route relations reflect essentially where you’d go if you wanted to “clinch” the old alignment of a route without straying too far from a current highway and trespassing on private property. By now, some of NE2’s route relations remain, and some have been deleted. They’ve released their work into the public domain, but I’m not sure we’d be able to use it directly anyways. More likely we’d consult the sources they cited in OSM (which OSM has no proprietary rights to).

Yes, many state DOTs maintain extensive libraries of old highway maps, route logs, and minute orders. If you let them know what we’re up to, they’ll probably bombard you with more than you’ll know what to do with. ![]() On the other hand, some of the states’ older maps are extremely crude, a far cry from today’s GIS layers and straight-line diagrams.

On the other hand, some of the states’ older maps are extremely crude, a far cry from today’s GIS layers and straight-line diagrams.

Old topographic maps are also very useful for tracking road development, with the caveat that the USGS was sometimes a few years behind the construction of some major roads, depending on when they got around to updating a given quad. Unfortunately, we haven’t integrated the USGS topoView layers into iD yet, but there is a manual workaround in this ticket:

In my limited highway mapping so far, I’ve started with roads I know well. For freeways, I track down articles in newspaper archives about groundbreaking ceremonies and ribbon-cuttings, then trace from modern aerial imagery, cross-referencing the built-in Esri Wayback imagery and USGS topo map layer to make sure I’m not glossing over a realignment that has taken place since opening.

Many freeways used to be known primarily or exclusively by a conventional road name, distinct from any route number or memorial name designation. These conventional names can be very useful for finding articles about freeway openings. For example, Interstate 275 in Ohio is formally known as the “Circle Freeway”, but this name has never been signposted anywhere. Roadgeek sources tend to gloss over this name in favor of the memorial name designation based on it, “Donald H. Rolf Circle Freeway”, that is minimally signposted. Yet references to “Circle Freeway” abound in newspaper archives, years after Rolf was honored in this way, often without mentioning I-275.

For other highways, I’ve found the AARoads Wiki (née English Wikipedia) to be useful starting point for research, since many articles contain sources with precise dates. However, there are also many undersourced articles that one can only take with a grain of salt. I’m hoping to interest the AARoads Wiki folks in building up OHM’s highway coverage in concert with their article editing.

I’ve also mapped some city streets, which can serve as a backbone for mapping route relations through town. In any city laid out as a neat grid, I’d start by determining when the town was first platted and mapping the grid en masse. Name changes and closures of specific street segments are often mentioned in passing in the context of something else, like an annexation or urban renewal project. In one area where I map, there used to be a local newspaper column called “How Was It Named?” that will be a boon for mapping street name changes, once I get to it.

We shouldn’t fudge any dates or rely on impossible leap days or future dates. These practices are brittle and difficult for data consumers to detect and filter out. Instead, let’s use start_date:edtf=* to record any uncertainty about dates, such as 1957?, 195X (1950s), or 1957/1959 (between 1957 and 1959). Then start_date=* can be a “resolved” date within the range specified by start_date:edtf=*, just for the purpose of having something to render.

Auto trails like the Lincoln Highway would’ve been good candidates for highway=trunk until the development of the U.S. Numbered Highway System. Many roads were part of both an auto trail and a U.S. Route, so the highway=trunk classification would’ve persisted in general, though the precise routing through cities would’ve varied a lot over time.

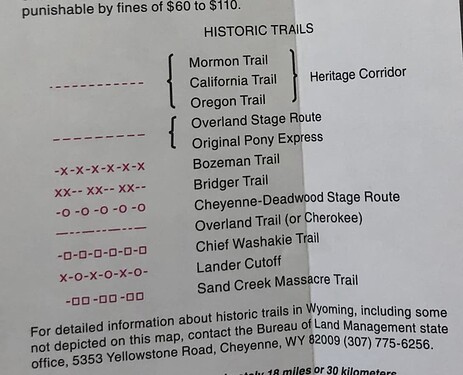

Some of the auto trails predate automobiles, so that’s a nice way of extending highway=trunk even further back in time. The National Road (Cumberland Road) overlaps with stagecoach routes in the West, which are also similarly prominent. Wyoming’s official transportation map prominently denotes historic stagecoach routes, so there’s probably decent sources for many of them, either as maps or in textual form:

Yes, I’ve seen folks sticking route numbers in ref=* or even name=* on individual highway=* ways, but I think of that as nothing more than a shortcut, just to jot down the information without losing track of it. Route relations are much more versatile for this purpose. As in OSM, you can add a given roadway to multiple route relations. But in OHM, these route relations can also represent the same route in different time periods.

OSM’s U.S. community has been talking about way refs as a deprecated or at least outmoded tagging scheme for 14 years now. In fairness, route relations are more complex to manage than way refs, but once our renderer starts processing route relations, it’ll be possible to do something more intelligent with them, like rendering historically accurate route markers in a road atlas style.