Thanks for this deep dive – I’m not terribly surprised to see that there’s more to the story. Were any of these changes considered to be retroactive? How should we handle retroactive boundary changes? (Ohio was legally established in 1953, retroactive to 1803.)

I’m not sure & that’s a point worth clarifying. I do believe the retroactive nature of any ruling applies to legal force of any conflicts that resulted from disputes over boundaries. Not sure it should change how things are mapped. I can see arguments either way. Should our map show the lines as best known at the time? Should we just map both and create a disputed area relation?

For simplicity of mapping I’ve started drawing boundaries at the 3nm distance, especially when the shoreline is very cragged or has lots of islands, and when the coastline is simple then I follow the coastline. And for modern day maritime boundaries I only map them if it’s the current country, and I would suggest they should only be mapped since they were created in the 1950s. I would suggest that a page should be created on the wiki of preferred methods, pros and cons of the different methods so that new mappers can be pointed to that page.

“The Historical Origins of the Three-Mile Limit” (1954) by H. S. K. Kent goes into exquisite detail about the origins of the traditional maritime limits. This is good background reading for anyone working on premodern national boundaries. Here are some notes I took in case it’s useful for your recent empire mapping. If not, maybe it would entice someone to map this maritime history too.

Originally, European countries reserved control within any territory from which one could still sight land – the “opposing coasts” principle.[1] In 1610, in a dispute with Great Britain, Holland claimed the “cannon-shot rule”. This variable distance was formalized as 3 nautical miles by the mid 18th century. By the 17th and 18th centuries, Mediterranean countries also used this standard. By contrast, Scandinavian countries including Denmark–Norway and Sweden claimed 1 Scandinavian league, which was standardized as 4 nautical miles in the 17th century.[2] Great Britain held firm to the cannon-shot rule except for recognizing Denmark’s 1-league claim in 1763.

The article focuses on Denmark–Norway to advance an argument that, although the 3-nautical-mile definition came from the application of the cannon-shot rule, the concept of a maritime belt of standard width came from Denmark, as a concession from their much more expansive claims based on the opposing coasts principle.

From the 16th century to the 18th century, Denmark–Norway claimed a continuous sea domain between their possessions, stretching from Norway to Iceland and eventually Greenland. In practice, Denmark ceded exclusive control of much of the northern sea to Holland in the 17th century and later England, France, and Russia. The high seas remained part of their claim but they no longer had “on the ground” control of it.

Throughout this time, Denmark continued to defend exclusive control over a belt around their possessions, primarily for fishing rights but later for trading and neutrality. This belt varied in size by possession and over time:

- Denmark:

- 1691-06-26: “the sea between the south coast of Norway and the coast of Jutland within a straight line drawn from Cape Lindesnaes, i.e., The Naze, to “Harboore” in Rinkjøbing, i.e., the west coast of Jutland”; otherwise, 4 to 5 leagues

- 1744: 4 leagues

- 1745-06-18: 1 league from outermost reefs (recognized by Great Britain in 1763)

- 1756-05-07: 1 league, baseline unclear

- 1759-02-23, 1759-04-20: clarified Scandinavian league of 4 nautical miles, not Continental league of 3 nautical miles

- 1761: 3 nautical miles recognized by France

- 1812-02-22: 1 league from farthest unsubmerged rocks

- Norway:

- 1636: 4–6 leagues

- 1692: 10 leagues

- 1743: 1 league off Finmarken

- 1747: 1 league

- Faroe Islands:

- 1616: in sight of shore

- 1618: 14 nautical miles according to Scotland; 4 leagues according to Denmark

- 1733: 4 leagues

- Iceland:

- 1598: 2 leagues

- 1648: 8 leagues

- Later: 6 leagues

- 1682: 4 leagues

- 1733: 4 leagues (Dutch and other MFN fishing vessels allowed to disregard this limit 1762–1836)

- 1836: 1 league

- Greenland and Spitsbergen (Svalbard):

- 1691-06-26: 4 leagues

- 1812-02-22: 1 league from farthest unsubmerged rocks

- Danish West Indies:

- 1757-05-13: 1 league, baseline unclear

Sweden followed Denmark–Norway’s lead:

- 1756-03-08: in sight of shore

- 1758-10-09: 3 nautical miles from farthest unsubmerged rocks

- 1779: 4 nautical miles

This continues to be a common law principle governing local jurisdiction over smaller bodies of water in some regions. ↩︎

Have fun converting to historical definitions of the nautical mile. ↩︎

One other element of this discussion is how we will handle requests for exporting polygons of political boundaries that include the actual shoreline instead of the maritime boundaries. I expect that this could be done any variety of ways, but hopefully we can just replace the maritime boundary part with the actual coastline. Right now, this doable externally (e.g. in QGIS), or, in the future, through some automated means.

Is there a tool to generate 3nm boundaries?

You could buffer the coastline in QGIS, but that’ll be more of a simulation than the actual boundary, which technically should be based on specific control points. For modern-day boundaries, it would be better to find a more explicit source of maritime boundaries, but a cruder approach is fine for older boundaries.

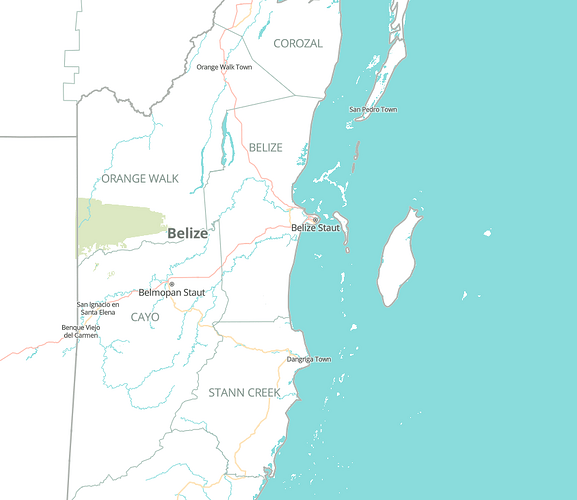

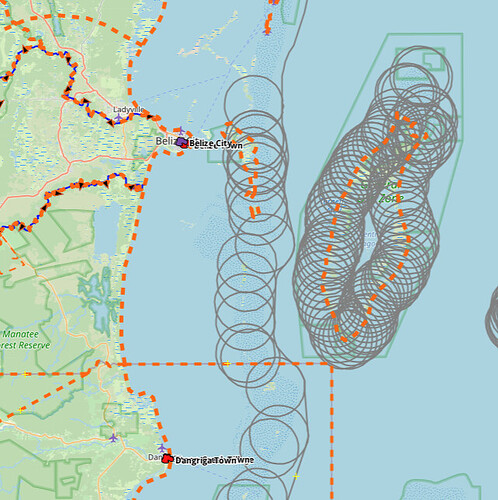

I’m just a bit torn on how to map the boundary of Belize. Especially historically. Do I draw 3nm from the coastline, or 3nm from the outer islands… Or do I leave it as is, and just merge the boundary with the coastline…

I can generate (or acquire) a 3NM boundary line for you, but @Minh_Nguyen is correct - modern maritime boundaries work off a “baseline” shoreline with other control points and lines.

For the sake of current rendering… and the way our system will work in the future to handle these boundaries, I highly recommend / encourage the use of 3NM offshore boundaries, even if that means including an island as sort of a separate outer ring in your relation.

I would like that. As for modern maritime boundaries, I will map them once I take some time to figure out the date they were officially introduced in Belize. And historically as part of the British Empire I did look it up it was 3nm, so I am assuming that applies for Belize as well.

Tangentially related to maritime boundaries - many counties historically had boundaries based on rivers/lakes, without any survey monuments being placed. Of course, rivers change with time - does that mean that river county boundaries on OHM ought to have an update for every year, considering the constant shifting course of rivers? Or should we stay within the conventions of the Atlas of Historic Boundaries, which uses modern waterways?

The issue is that the work required to update county boundaries for every year is much more than the payoff, which would be a minimal shift in the boundary. Add that to the fact that many features used to describe boundaries were never precisely or accurately mapped before the modern era, and it creates a conundrum. One county boundary (Yuba-Butte in CA) was defined by a watershed which has now shifted, and the modern version results in it being up to 0.5 km off the boundary I determined from an early 1880’s topo map in some areas.

The Newberry Library dataset we imported was in many ways optimized for visualizations at smaller scales than we increasingly care about as we turn our attention to more local boundaries and other features. They also optimized the dataset to be viewed as an isolated layer rather than integrated into a well-rounded historical dataset like we’re trying to build. As a rule, they didn’t include any large bodies of water in county boundaries, which sometimes resulted in feature metadata noting discrepancies like certain boundary changes being totally “unmappable”.

In Anglo-American legal systems, whether a jurisdictional boundary changes with a waterway depends on the language of the boundary description and the circumstances surrounding the change. Courts seek to distinguish avulsion from accretion, which doesn’t always come easy.

To the extent you’re able to track down sources explaining any notable shifts, you can feel free to record them and reflect them in the boundary. But it’s also acceptable to temporarily skip some details for the sake of keeping the boundary manageable. Make sure to note any errata in note=* and fixme=* tags, akin to what the Newberry Library did. In time, we may have a reason to track certain boundaries more granularly based on accretion, just as we track some boundaries during wartime based on shifting front lines.

@jeffmeyer would you want to take a look at my mapping of Maritime boundaries in Central America? It’s still a work in progress.

Will do - I’m cranking on some stuff for State of the Map in Boston ;), but I’ll take a look when I can. It might be a few days.

So I’m mapping the French possessions in North America and now I’m thinking of using the 3nm boundary in the Great Lakes as the boundary line.

Unless you find some document to the contrary, I suspect that any international boundary through or along the Great Lakes would be arbitrary and indefinite until at least the Jay Treaty of 1794, which set up the International Boundary Commission.

Even under later American jurisprudence, a domestic border wouldn’t automatically extend to the centerline at common law, because the lakes are too big to see across, while at the same time I haven’t found any mention of cannonshot-rule boundary such as 3 nautical miles. When I extended county boundaries into the lakes, I only did so based on legal redefinitions that explicitly included the lakes, but otherwise I left older county boundaries hugging the lakeshore to avoid overstating anything.

It’s less awkward for domestic boundaries because there’s a notion of unorganized state or federal territory. But if you want to avoid a gap between countries, the best approach might be to run an international boundary down the centerline and tag it as indefinite=yes. This way would need to be distinct from the modern-day one. You could also add a fixme=* for someone with more expertise to follow up on.

This is intriguing. For Yuba-Butte, did you create an original and then current set of boundaries here? I’m wondering about the accuracy of the early 1880s topos and whether there might be accompanying survey data. I can’t imagine at least half of the landowners would take too kindly to a reduction in land ownership.

Regardless of the answer above, improving the quality of the county boundary data is amazing and super helpful. Kudos to you for digging deeper and thank you!

Looking at these 3-nautical-mile boundaries within the Great Lakes in 1725, I wonder if this would mislead readers into thinking we have more precision than we really do. A straight shot across the lake wouldn’t be precise either, but at least its precision is more ambiguous. How do contemporary and modern maps depict the boundary during this time period, if at all?

I agree it looks weird. Maybe I should draw a boundary that’s more or less the center line of the lake, but not the same boundary that’s used today. That one is too straight.